Appaloosa Territory

Home | Appaloosa History

Appaloosa History:

Checking Out The Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw

by Sherry Byrd

It is historically recorded that the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw tribes on the East Coast were known as excellent horsemen and "avid horse breeders who had herds of horses with qualities sought by the white settlers as early as the late 1600s. In other words, the Nez Perce were not the only "horsemen" tribe known for their horse breeding, nor did they have the only quality horses as the ApHC myths have stated for decades. One person described the Chickasaw as being elegant like a deer, which seems to be a big difference to Lewis and Clark's "courser" description of the Nez Perce horse.

In disagreement with the ApHC's promotion of the Appaloosa was bred and developed in the Pacific Northwest and only the Nez Perce had and bred them, this research will provide historically recorded information that other tribes also had spotted horses, including the Chickasaw, Cherokee, Choctaw, Comanche, and the Huasteca (Mexico).

CHICKASAW

The Chickasaw tribe lived in what is now Mississippi, Alabama, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The Chickasaw horses are in fact considered a part of the basis of the East Coast running quarter mile horse, aka the Quarter Horse. These horses were proven to be good all-around utility horses and were much favored by the settlers. Robert Denhardt stated the Chickasaw were inclined towards permanent settlements and pursued agriculture to some extent, which made them ideally suited to raising horses over the semi-nomadic western tribes. The Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw exchanged horses, as all three tribes, as well as the Creeks, were noted horse breeders. Historical records describe some of these horses as vari-colored or calico, and their herds also contained solids, paints, leopards, and blankets. Horse breeders in Kentucky and Tennessee had Chickasaw 'Indian pony' blood in their mares. The breeding centers that developed around Nashville and Lexington were the source of the best blood for decades and were the primary source of the foundation stock in the new western states. The Chickasaw had their "Trail of Tears" in 1837 when it was ordered, under the auspices of Andrew Jackson's 1830 Indian Removal Act, that they be resettled among the Choctaw tribe in Indian Territory. The Chickasaw, as well as the Cherokee and the Choctaw all took horses with them on their respective "Trail of Tears" to the Oklahoma Indian Territory.

Francis Haines, so-called Appaloosa historian, steps into the discussion of the Chickasaw horses with his typical misinformation and lack of proof. In a letter to Thornton Chard, noted equestrian scholar in the early 20th Century, who was studying the Chickasaw Horse, Haines makes the following remarks….

"It is well to keep in mind that the woods Indians along the {Mississippi} river did not use horses, and the Chickasaws would have had to travel a hundred miles west of the river to buy their animals. Although I have no proof (written contemporary records) I doubt that this traffic developed before 1750, because of the danger from hostile tribes, the difficult natural barriers of timber, swamp and river to be crossed, and the difficulty of ferrying [horses] in Indian canoes. Until 1800 the chief source of supply of horses to the Indians east of the Mississippi was, most probably, the Spanish Missions in Northern Florida and Southern Georgia”"".

Robert Moorman Denhardt notes Haines' above quote in his book The Quarter Running Horse, and tends to agree with him that it was unlikely that the southeastern tribes got horses west of the Mississippi. It is somewhat presumptuous of Haines to tell Thornton his version of the Chickasaw horse history (with no proof), when Thornton was such an equestrian scholar. One of his research articles titled "Did the First Spanish Horses Landed in Florida and Carolina Leave Progeny?, was presented to the American Anthropological Association in 1940. This research article featured 50 footnotes and 5 Appendices. The article concluded that there was no progeny from the horses of the first Spanish explorers (Columbus, DeSoto, LaSalle and Ayllon). The conclusion was drawn from actual expedition records that recorded the deaths of the horses, how many were eaten, and because the horses were valuable that the Spanish always took the remaining horses back with them. There was also the custom that mares were seldom taken on exploratory expeditions. Thornton alludes to Haines' belief that there were no horses prior to 1630 in his research, while noting the "true Chickasaw Horse" (1740-1786) was originally from the plains west of the Mississippi. So it seems that history was NOT one of Haines' strong points.

On that note, Paul Laune's book America’s Quarter Horses, states that the Chickasaws were riding horses by the 1690s and that they had their best horses between 1700-1740, which were being obtained from the western plains instead of being bred locally. The Chickasaws, allies of the English, got their horses from the Choctaws, allies of the French, from mostly raiding. The Choctaw horses were mostly sourced from French horse traders in Natchez and Mobile Bay, who sometimes sources their horses from Spanish stock found more westward. So Laune contradicts Haines on several points: 1) the woods Indians did not have horses; 2) Chickasaws did not "buy" their horses from west of the river; 3) the natural barriers were not a hindrance for the Choctaws to get horses west of the river; 4) the Choctaws' chief source of horses were the French horses from the Choctaws and not Spanish horses from the south; and 5) the Chickasaws had horses over 100 years before Haines thinks they did. So again, Haines flunks history.

Yet another book, Know The American Quarter Horse by the Farnam Horse Library Series, says the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians stole horses from the Spanish settlements in Florida, and many years later the Chickasaw Indians in the 1600s traded those horses to the planters and settlers in the Carolinas.

Nelson Nye discussed the Chickasaw horses in his book The Complete Book of the Quarter Horse, tying the Chickasaw into the development of not only the early Quarter Horse but also the early American TB. Both had identical blood, but their "breed" was determined by the race track and distance. Nye says the Spanish horses that were in the early colonies have always been taken for granted that they came from the horses of DeSoto, Cortez, or other early Spanish explorers, but in fact these "Barb" horses came from what was called "Spanish Gaule" (Florida), which in 1650 had 79 missions, 8 towns and 2 royal ranches. The Chickasaw Indians got these "Barb" horses by various means and would later provide these horses to Carolina planters. The Chickasaw bred these horses for many years and before 1754 these horses were the most regarded horses in South Carolina for draft or saddle use. As previously stated by Nye the Chickasaw horses helped build the American TB, as the imported "running horses" from England (not yet considered as TBs) like *Janus and many other stallions were bred to Chickasaw mares. The products of such breedings would form the basis of the American TB and the QH breeds. Nye also comments that the QH was used extensively to "increase the popularity" of the Appaloosa horse.

Walter Osborne's book The Quarter Horse also discusses the Chickasaw horses and their contribution to the development of the QH. Osborne notes the importance of the early blood-horses or early running horses (pre-TB), like imported *Janus and Flimnap being bred to the native Chickasaw mares to develop the quarter mile racers that would become the American Quarter Horse. Osborne states that the myth of the Chickasaw horses being descendants of DeSoto or Narvaez has been "thoroughly exploded", which of course disagrees with Haines' decades-long unsupported theory of the influence of the early Spanish explorers' horses. Osborne also brings up the theory that the Chickasaw horses came from Spanish outposts in Mexico and the American Southwest and moved eastward from tribe to tribe to the southern states.

In his book Quarter Horse A Story of Two Centuries, Robert Denhardt states that the Chickasaw got their horses (refers to them as ponies at one point) from the Guale (Gaule) Spanish settlements and from the Cherokees of the southwest and southeast. Denhardt gives several sources for his Chickasaw information – article "Romance of the Western Stock Horse", Western Horseman, April 1936; Travels in the American Colonies by Adam Gordon (1764); A Tour of the United States of America by J.F.D. Smith (1781); and the article "Quarter Horse and Chickasaw", Western Horseman, July 1942.

Denhardt, in his book The Quarter Running Horse, notes that it was because of the Chickasaw (and Cherokee) mares, that the imported stallion *Janus got a bad reputation in that his get "had no bottom and could not go the distance". The native mares bred to *Janus were considered "ordinary" because they had no English racing blood. It is interesting to note that *Janus’ progeny from blooded clean-bred mares were excellent ‘stayers’ of which *Janus was a noted sire. Yet when bred to the Chickasaw and Cherokee "ordinary" mares, his progeny were noted as the best short distance horses there were to be found.

In the Saga of the American Quarter Horse Genealogical History 1752-1941 by Barbara M. Huntington, the author barely mentions the Chickasaw horses or people except to say the Chickasaw tribe kept the settlers stocked with Spanish horses from Florida and that the Indians loved horse racing. Huntington appears to be a follower of the escaped Spanish horses populating the American West, claiming that the Spanish horses were all breeding stock and thus multiplied to 1 1/2 million head. Near the end of her book, she credits the Chickasaw with helping create the Quarter Horse, along with Oriental, Thoroughbred, and Spanish Mustang blood.

CHEROKEE

The Cherokee were noted as avid horse breeders for many years during the 1700s, producing good all-around utility horses. Robert Denhardt thought that the Cherokee were inclined towards permanent settlements and pursued agriculture to some extent, which made them ideally suited to raising horses over the semi-nomadic western tribes. Their tribal horse, like that of the Choctaw and Chickasaw were described as "excellent". Their horses, having shared stock with the Choctaw and Chickasaw, were a variety of colors including solids, roans, calicos, paints, leopards and blankets. In his book Quarter Horses A Story of Two Centuries, Robert Denhardt states that the horses of the Cherokee (and Chickasaw) were as "thoroughly bred" in their own way as were the imported English horses, only their source was Spanish and not English. Denhardt, in his book The Quarter Running Horse, notes that it was because of the Cherokee (and Chickasaw) mares, that the imported stallion *Janus got a bad reputation in that his get “had no bottom and could not go the distance”. The native mares bred to *Janus were considered “ordinary” because they had no English racing blood. It is interesting to note that *Janus’ progeny from blooded clean-bred mares were excellent ‘stayers’ of which *Janus was a noted sire. Yet when bred to the Chickasaw and Cherokee “ordinary” mares, his progeny were noted as the best short distance horses there were to be found.Denhardt also states that the Cherokees from the southwest and southeast furnished horses to the Chickasaws. Denhardt refers to H.D. Smiley’s article “The Cherokee Side of the Quarter Horse” published in the December 1954 The Quarter Horse Journal, along with the article ‘Romance of the Western Stock Horse, published April 1936 in Western Horseman, and Adam Gordon’s Travels in American Colonies published 1764 as sources. Horse breeders in Kentucky and Tennessee had Cherokee ‘Indian pony’ blood in their mares. The breeding centers that developed around Nashville and Lexington were the source of the best blood for decades and were the primary source of the foundation stock in the new western states.

Most people are familiar with the Cherokee for their historical Trail of Tears forced move in 1835 (or 1838 depending on source) to Indian Territory across the Mississippi River. But much history of the Cherokee prior to that point has not been told and what hasn't been told could be quite important to "horsedom"". Also it should be noted the name Trail Of Tears started long before the Cherokee, with the forced removal of the Choctaw in the winter of 1831 to Indian Territory in Oklahoma and followed by the removal of the Creek Indians in 1836, and the Choctaw in 1837, all under the directives of Andrew Jackson's 1830 Indian Removal Act. The Cherokee, as well as the Chickasaw and the Choctaw all took horses with them on their respective Trail of Tears to the Oklahoma Indian Territory. The Trail of Tears in actuality was a network of many different routes that covered more than 5,000 miles through the states of Georgia, Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, Illinois, Oklahoma, and Missouri. The Cherokee has been erroneously and solely connected to the Trail of Tears as the Nez Perce has been to the Appaloosa.

The facts are that Cherokees moved westward long before the tribe's forced removal. In 1819 some 3,000 families of western Cherokees crossed the Mississippi River into Missouri and Arkansas Territory. This 1819 move of some of the Cherokee was done under a treaty between the Osage and the Cherokee. This treaty was governed by Captain William Clark (as in Lewis and Clark), who was the Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1822-1839. By 1827 over 10,000 Cherokees had moved under this treaty. Due to continuous attacks by the Osage who did not respect the treaty, some of those 10,000 moved into Texas Territory under a land grant, known as Cherokee County, from the Mexican government. Others went into Mexico, near present day Tyler, Texas in 1830. When Texas became a state, these Cherokees were forced to move back to Missouri and Arkansas, with some going to Oklahoma Territory. These Cherokees would refer to themselves as "Black Dutch" or "Low Dutch" (claiming their birth place as Tennessee or Iowa), to blend in with the whites. It is interesting that the western Cherokee considered the area of present day Ozarks to be their traditional homelands.

The first large Cherokee movement to the Ozark region was in 1694, due to the refusal to acknowledge the treaty with the British colony of Carolina. Other tribal members moved throughout the late 1600s into the early 1700s as British settlements increased. Another major emigration happened in the 1720s which divided the eastern Cherokee. Another group moved about the time of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Another group of the tribe also moved in 1782 to Spanish territory west of the Mississippi River into the Western Ozark region along the Arkansas River. In 1785 and 1794 other groups settled along the White River, close to what is now Oklahoma. Eastern Cherokee migrated into north central Arkansas in 1808, joining relatives who had been there since the 1770s. A group of eastern Cherokees moved into north central Arkansas and south central Missouri after refusing to agree to the 1775 British Treaty of Sycamore Shoals.

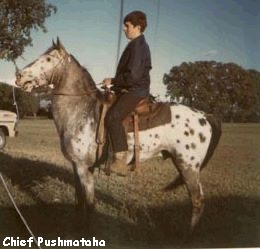

What matters with any of this is that the migrating Cherokees took their horses with them. Therefore this Cherokee stock that had been noted for its quality was scattered throughout Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, Oklahoma. One group of the migrating western Cherokee became the Kiamichi Band. The name “Kiamichi” can be found in Spanish Mustang (SSMA and/or SMR registries) pedigrees, as with the stallion Chief Kiamichi or the stallion Kiamichi Mountain SSMA 44. Kiamichi Mountain is the sire of the ApHC registered Spanish Mustang stallion named Chief Pushmataha ApHC T21400/SSMA 60/SMR 47. Chief Pushmataha has progeny registered in the ApHC as well.

There is a bloodline of Cherokee horses known as the "Whitmire line". The Cherokees bred their horses with emphasis on the mares' lines, keeping that side of the pedigree within the herd throughout the years. Although it was preferred that stallions be from within the herd as well, sometimes outside stallions of Mexican, Choctaw or Comanche lines were used. The Mexican lines were known to have leopard patterns, and were probably from the Huasteca tribe in Mexico, who were known for spotted horses, particularly leopard patterns. Of the Comanche based stallions, the horses from the Black Moon Comanche band were known for leopard types as well.

Prior to and after the emigrations, there was always travel to trade areas. The Spiro Mounds (Oklahoma) were a major trade center for many tribes. The Cherokee went to the Great Lakes area for copper. The Cherokee even traveled to the Rocky Mountains for trading.

CHOCTAW

The Choctaw Indians originally lived in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Like their neighbors, the Cherokee and Chickasaw, they were known as avid horse breeders. Their tribal horses like those of the Cherokee and Chicksaw, were described as an "excellent horse" as far back as the 1700s. Their horses consisted of a variety of patterns including solid colors, calicos, roans, leopards, blankets and paints. Dr. Philip Sponenberg, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine has worked with the breed of horses, and states they are descendants of horses brought to the U.S. in the 1500s. In the book The Quarter Horse, Walter Osborne lumps the Choctaw and Chickasaw horses together, as both having Spanish origins and being larger, and of better quality and temperament than the Seminole or Creek horses said have the same origins but lacking in size and disposition. This tribe had their Trail of Tears in the winter of 1831, under the orders of Andrew Jackson's 1830 Indian Removal Act, years before the Cherokee. The Choctaw, as well as the Cherokee and the Chickasaw all took horses with them on their respective Trail of Tears to the Oklahoma Indian Territory.

Choctaw lines are quite numerous in the pedigrees of Spanish Mustangs (SSMA and/or SMR registries). Some of these lines are of named horses, although many lines are simply noted as Choctaw stallion, and Choctaw mare. There are many descriptions of Appaloosa patterned Spanish Mustangs as well as Pintaloosa Spanish Mustangs in the registration records of the SSMA and SMR, with these lines tracing back to Choctaw stock. One stallion, Choctaw Sundance SMR 1282, is described as a pintaloosa. Another stallion, the ApHC registered Spanish Mustang named Chief Pushmataha ApHC T21400/SSMA 60/SMR 47 has a lot of Choctaw stock, but no actual “Nez Perce Appaloosa” in his ancestry. Chief Pushmataha has several progeny registered in the ApHC.

OTHER...

One might also consider the moving of the Fox (Meskwaki) and the Sac/Sauk (Thakiwaki) Nation into Indian territory in 1870. The Sac and Fox tribes were originally two separate groups, but joined forces into one alliance due to attacks by the French in the 1700s. The Sac and Fox Nation was originally located in the Saginaw Valley near Lake Huron and Green Bay of Lake Michigan. The Sac and Fox first moved to Illinois, staying there from 1764-1830, then moved to Iowa from 1831 to 1846. The tribes split with some moved to Kansas from 1847-1867 and some to Nebraska and Missouri, and finally to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma, under the directive of Andrew Jackson's 1830 Indian Removal Act.

In an article titled "First Appaloosa?" by Claude Thompson (no source or date – Thompson was ApHC President at the time), Thompson talks about a leopard stallion called Nibs (died 1904), owned by Abram Vosberg, originally from Albany, NY and longtime resident of Belle Plaint, Iowa. [Note: the name is actually Belle Plaine, Iowa]. Vosberg bought Nibs north of the Sac and Fox Reservation in Iowa in the 1880s. Vosberg drove Nibs from Iowa to New York, breeding mares along the way. Unfortunately his breeding records were lost according to Vosberg's daughter.

Thompson spends quite a bit of time extolling his theory of the close connection of the Appaloosa and the Arabian and that many early Appaloosas "carried much Arabian blood". Thompson also pointed out that Appaloosas used to be called Arabians in the East and Midwest. Thompson thought the Appaloosa descended from the Kehilan Krush strain of Arabians (Egypt) because they have the same "white around the pupil of the eye". The actual strain is called Kuhaylan al-Krush or Kuhaylan Krushan, and records show none were imported to the U.S. until after 1900. Homer Davenport imported one in 1906, a mare named *Werdi.

Thompson was given a photograph of a painting of Nibs, who Thompson claims was referred to as an Arabian. Thompson praises the artist who made the painting for extolling many Arabian characteristics in Nibs, then goes on to say that the artist probably never saw an Arabian to know what one looked like. Thompson also theorizes that Nibs' "ancestors came from Indian stock in the Dakotas and perhaps even from the Northwest".

Thompson goes on to say that Nibs reminded him of an Appaloosa owned by one of his uncles in the 1890s. This horse was also a leopard (with black spots on his rump), and was called Dude. Dude's dam was a red roan Appaloosa mare that Thompson's grandfather had gotten from the Indians someplace in route across the plains to the Pacific Northwest almost 100 years ago.Thompson claims that Dude showed "definite signs of Arabian blood although his sire was a grade Percheron".

OTHER...

The Creek or Seminole Indians also had access to the Spanish horses through contact with the Spanish in Georgia and Florida. These horses would also go into the making of the "short horse" in the Southeast, although not to the extent of the Chickasaw and Cherokee horses. The Seminole had Creek in their mixed origins, but later broke all connections with the Creek tribe by the beginning of the 19th century.

The Seminole had their own Trail of Tears although it was quite different than that of the other “Civilized Tribes”. The Seminoles were forced off of their land and into the swamps in multiple occurrences, with removal beginning in 1830 with the passage of Jackson's Indian Removal Act. From 1830 -1832 Seminoles were hunted and any captured were sent to the Oklahoma Indian Territory. In 1833 the Treaty of Ft. Gibson brought mass removal of the Seminole into the Creek Nation in Indian Territory, forcing the Seminole to live with the Creeks which they did not like or get along with. The Seminole removal differed in that they were moved by boats across the Gulf of Mexico and then up the Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers to Little Rock. There they were taken off the boats and put on horses to travel from Little Rock to Ft. Gibson. It is not recorded if their horses went with them on the boats, or where the horses came from that took them to Ft. Gibson.

With the influx of many tribes and their horses into the Oklahoma Indian Territory, particularly the famed Chickasaw and Cherokee stock, Oklahoma would later become an important location for horse breeding, years after Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky whose horse breeding fame was based upon the same Chickasaw and Cherokee stock. Later cattle ranches would lease Indian territory land to run large herds of cattle on. The Burnett and the Waggoner were among the first, leasing before 1889. Both ranches had their headquarters and horse breeding operations in Texas, but would purchase native stock to replenish their horses working the leased land. No doubt some of these Oklahoma native horses went to Texas into the major ranchs' breeding programs.

SOURCES:

- The Running Quarter Horse, by Robert Moorman Denhardt

- Horse Lover Magazine, August/September 1949, page 23; re: Haines letter to Chard

- America’s Quarter Horses, by Paul Laune

- Know The American Quarter Horse by the Farnam Horse Library Series

- The Long Riders Guild Academic Foundation; Re: article “Did the First Spanish Horses Landed in Florida and Carolina Leave Progeny?”, by Thornton Chard

- Personal research notebooks – Chickasaw horse, Cherokee tribal history, Francis Haines, Spanish Mustang,

- Cherokee Native Americans And Their Descendants – Face Book; Timothy W. Jones, Ph.D. Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ)

- https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

- Article– “Rare Horses Found in Mississippi, Descended from Line Bred by Choctaw Indians” by The Associated Press, 10-2018

- Article– “Choctaw Spanish Mustangs, Heritage Horse of Oklahoma, Arrive at Jones Academy”, by Mike Cathey, 10-2020; https://www.mcalesternews.com

- https://www.sacandfoxks.com ; Sac and Fox Nation of Missouri in Kansas and Nebraska

- ApHC Stud Books

- Article– “First Appaloosa?” by Claude Thompson; no source or date; received from Cheryl Palmer 6-2015

- https://www.daughterofthewind.org/kuhaylan-al-krush-a-refresher/

- The Complete Book of the Quarter Horse by Nelson C. Nye

- The Quarter Horse by Walter D. Osborne

- Quarter Horses A Story of Two Centuries by Robert Moorman Denhardt

- The Quarter Running Horse, by Robert Moorman Denhardt

- Saga of the American Quarter Horse Genealogical History 1752-1941, by Barbara Muse Huntington

Top

Back to Appaloosa History Index

This page posted February 2023.